Drowning is the process of experiencing breathing difficulties due to being under or in water or other liquid. Drowning results in a lack of oxygen reaching vital organs such as the brain and heart. The drowning process begins when the person’s airways lie below a surface of a liquid. Initially, the person attempts to hold their breath but then – unable to breathe air in – breathes liquid into their airways (Szpilman, 2012). If there is no rescue and they remain unable to breathe air, the person becomes unresponsive and their breathing and circulation systems fail.

Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injury-related death worldwide. There are an estimated 320,000 annual drowning deaths worldwide (WHO, 2020). Global estimates may significantly underestimate the actual public health problem related to drowning. Incidence, circumstances and those at risk of drowning vary considerably worldwide. However, low- and middle-income countries account for over 90% of unintentional drowning deaths. Most drowning accidents occur in ponds, ditches, lakes, rivers and the sea. The drowning mortality rate for men is twice as high as for women overall (WHO, 2020).

Guidelines

- Rescue equipment such as throw ropes or ring buoys (life belts) can be used effectively by first aid providers to assist a person at risk of drowning.*

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be started without delay on a person who is unresponsive and has abnormal breathing (e.g., taking irregular or noisy breaths, or they have stopped breathing altogether) as soon as they have been removed from the water.**

- Rescue breaths should be provided as part of CPR to a person who has drowned and is unresponsive with abnormal breathing.*

- If an automated external defibrillator is easily accessible, it may be used on a drowned person who is unresponsive with abnormal breathing, but its use should not interrupt CPR. The pads should be applied to skin that has been dried.*

- In-water resuscitation (consisting of early rescue breaths and airway management) is NOT recommended for first aid providers. In-water resuscitation should only be attempted by rescuers who are specifically and repeatedly trained and practised in contact-rescue techniques and only in safe conditions.*

- Submersion duration should be used as an indicator when making decisions about search and rescue resource management or operations.**

Good practice points

- The first aid provider should be alert to danger and always prioritise their own safety.

- Drowning causes a breathing problem so first aid providers resuscitating a person who has drowned must prioritise upper airway management and early rescue breathing.

- Attempted rescue by a layperson should be made from land or boat, without entering the water, by reaching with something rigid (e.g. a pole or tree branch) or throwing a rope or buoyant object. The first aid provider should not touch the drowning person because there is a risk they may be pulled into the water.

- In the case that a first aid provider is already in the water and attempting a rescue, they should have some knowledge of the aquatic environment and use a flotation aid.

- The possibility of a spinal injury should not delay the removal of an unresponsive person from the water.

- A person who is unresponsive and breathing normally should be positioned or transported in the recovery position – lying on their side with their head positioned to allow free drainage of fluids from their mouth. Any pressure on their chest that may cause breathing difficulty should be avoided.

- If the person is unresponsive and has abnormal breathing, two to five initial rescue breaths may be given before compressions.

- If the first aid provider is trained and oxygen is available, the provider may give oxygen to a person who has drowned and is breathing normally.

- Supplemental oxygen for resuscitation of a person who has drowned may be used, but doing so should not delay CPR, including opening the airway and providing rescue breaths and chest compressions as needed.

- Manual methods to remove material in the airway of a person who has drowned should only be used when the airway is blocked by vomit or debris that is preventing breathing. Manual methods include using fingers to remove a visible foreign object from the person’s throat, or positioning the person to enable fluid or vomit to drain out.

- Education on this topic should help the learner to understand the drowning process and the importance of rescue breaths during CPR. Airway management skills should also be included.

- Parents, caregivers and habitual swimmers should be encouraged to have rescue equipment with them that they know how to deploy or use effectively.

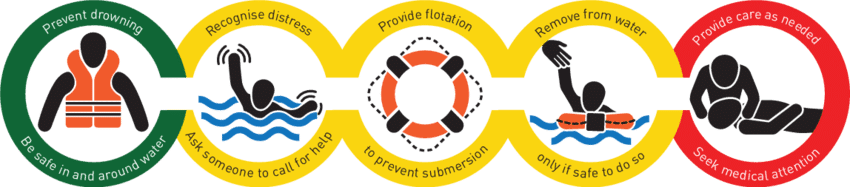

- Swimming courses should include all domains of the Drowning Chain of Survival (prevent drowning, recognise distress, provide flotation, remove from water and provide care as needed) to improve water competencies.

Drowning chain of survival

First aid for drowning incidents are often linked to demanding rescues, which endanger the life of the first aid provider. It is important to act quickly to restore breathing to the drowning person. For this reason, a problem-specific “Drowning Chain of Survival” was developed to define the key steps to providing a rescue (Szpilman, 2014).

Prevent drowning

The following measures can be adapted locally to reduce risk factors or strengthen protective factors related to drowning.

- Advocate that people install barriers to control access to water (WHO, 2017).

- Acquire water competencies and advocate that individuals have or improve their water competencies (swimming, floating, life jacket use, local hazard recognition, rescue, CPR) (Stallman et al., 2017).

- Teach school-age children swimming and water competencies (WHO, 2017).

- Provide safe places (for example a day-care centre) away from water for pre-school children, with capable child care (WHO, 2017).

- Train bystanders in safe rescue and resuscitation (WHO, 2017).

- Encourage caregivers to conduct a risk assessment prior to trips to or at bodies of water (Denny et al., 2019).

- Encourage caregivers (e.g., parents or other family members, daycare providers, teachers, youth group leaders, water sports or swimming coaches) to provide constant and close supervision of young children and inexperienced swimmers around, near and in the water.

- Encourage communities to engage in water safety programmes to build a collective understanding of the dangers and preventative strategies for activities in, on or near water.

- Build resilience and manage flood risks and other hazards locally and nationally (WHO, 2017).

- Advocate that safe boating, shipping and ferry regulations are set and enforced (WHO, 2017).

Strategies

- Strengthen public awareness of drowning through strategic communications (WHO, 2017).

- Promote multisectoral collaboration (WHO, 2017). Work with other organisations to achieve greater reach and message harmonisation.

- Take part in or initiate a national water safety plan (WHO, 2017).

- Advance drowning prevention through data collection and well-designed studies (WHO, 2017). This could include evaluating the effectiveness of your own programmes.

Recognise distress

Drowning is a process that the first aid provider should try to recognise (and interrupt) as quickly as possible. Often the drowning person experiences a triggering incident, then loses control of their ability to breathe or move in the water. They may struggle and then submerge and breathe in water. The process is very quick, lasting from seconds to just a few minutes before the person can no longer surface.

The following may indicate a person is drowning:

- Behaviour or actions that do not correspond to the person’s abilities (e.g., a child alone in the water or swimming in a deep area).

- They do not respond to the question “Are you OK?”.

- Their mouth is below the water or they are gasping or spluttering.

- They appear to be struggling to breathe.

- Their head is underwater or they are face down.

- Their body position has changed from being horizontal (swimming position) to vertical (they may appear to be climbing an invisible ladder).

- They are pushing their arms down like a watermill on the surface of the water.

- The person is trying to swim in a particular direction but making no progress.

- The person is not moving in any direction but bobbing up and down.

- The disappearance of a person last seen in the water.

_____________________________

NOTE

Drowning is often quiet. A person who is in distress may not wave or call for help. Quick recognition is crucial for a positive outcome following a drowning incident.

_____________________________

As soon as it is recognised that a person is in distress, the first aid provider should ask for help from other bystanders, lifeguards or emergency services. If possible, someone should stay on the scene and constantly observe where the drowning person is in the water.

Provide flotation

If the drowning person is responsive, the first aid provider should provide flotation to keep the person’s airway above water. This buoyancy buys time for their removal from the water.

The first aid provider should stay out of the water, providing flotation from a position of safety. The human motivation to help, especially of relatives and friends, exposes the first aid provider to a significant danger of drowning that can cause death (Franklin & Pearn, 2011). Their primary focus should be on maintaining their own safety.

Flotation can be provided by reaching out to the person with an object (e.g. a pole, tree branch or towel) or by throwing something that floats (e.g. a buoy, floating boxes, life-jacket or anything else that floats).

In situations where the first aid provider is already in the water (such as on a surfboard or kayak) and has appropriate characteristics (good aquatic competence and experience, physical fitness) and some type of flotation aid, they may attempt a rescue before calling for help.

Remove from the water

The best way to remove a person will depend on the situation including the condition of the person to be rescued, available equipment, type and accessibility of the water body, and availability of other bystanders.

The first aid provider could pull the person to land or a boat using rescue equipment such as a pole, rope, or flotation aid and then pull the person out of the water.

If the person cannot be reached with rescue equipment a water vessel or equipment (such as a boat, jet ski, surfboard, canoe or kayak) could be used to reach the person.

Swimming to reach the drowning person is associated with high levels of danger for the first aid provider – no matter if trained or untrained. Whenever possible, this should be avoided. However, if the situation develops in such a way that swimming to the drowning person is necessary, the rescuer should take a flotation aid.

If the drowning person is responsive they are likely to panic and may pull or grab onto any person or thing approaching them. For this reason, it is important to always provide flotation to the drowning person (see above) and use a flotation aid to protect yourself.

If the person is unresponsive, the same principles apply in that the first aid provider should protect their own safety and could attempt rescue using a boat or water sports equipment (canoe, kayak, stand up paddleboard, surfboard, etc.).

Provide care

Once the person has been removed from the water and is on land or a boat, check for a response, and open their airway and check for breathing. Treat the person according to their condition.

Responsive and breathing

- Help the person to rest in a comfortable position, preferably sitting or lying on their side.

- Carry out further assessment of their condition, see General approach.

- Keep the person warm by covering them with dry clothing and protecting them from the cold ground.

- Monitor the person closely in case the person develops breathing difficulties.

_____________________________

CAUTION

- Breathing difficulties can develop, so if possible, advise that someone stays with the person to monitor their condition for around 8 hours.

- If the person is experiencing breathing difficulties or coughing a lot, access medical care.

_____________________________

Unresponsive and breathing normally

- Move the person onto their side and tilt their head back (or into a neutral position if it is a baby) to maintain an open airway and help fluids drain. This is called the recovery position. A baby can be held in this position in your arms. See Unresponsive and breathing normally.

- Access EMS and follow their instructions.

- Keep the person warm by covering them with dry clothing and protecting them from the cold ground.

- Monitor the person closely as their condition may deteriorate rapidly. The person may vomit or experience worsening breathing.

Unresponsive and abnormal breathing (e.g., taking irregular or noisy breaths, or they have stopped breathing altogether)

- Immediately ask a bystander to access EMS, or if you are alone, access EMS yourself. If using a phone, activate the speaker function.

- Open the person’s airway and give two to five initial rescue breaths. Blow steadily for one second until you see their chest or abdomen rise.

- If there is no response, give 30 chest compressions without delay; push down on the centre of their chest at a fast and regular rate (100–120 compressions per minute).

- Give two rescue breaths. Blow steadily into their mouth or mouth-and-nose for one second until you see the chest or abdomen rise.

- Continue with cycles of 30 chest compressions and two rescue breaths until emergency help arrives or the person shows signs of life (such as coughing, opening their eyes, speaking or moving purposefully) and starts to breathe normally.

_____________________________

NOTE

- The person is likely to vomit. Be prepared to roll them onto their side to clear their airway.

- While performing CPR, be alert to any signs of life such as movement or coughing. If you see any signs of life, pause CPR for up to ten seconds to see if the person can breathe on their own.

- If you are unwilling or unable to give rescue breaths, give chest-compression-only CPR at a rate of 100–120 compressions per minute.

- If an automated external defibrillator is available, ask a bystander to bring it as quickly as possible. Dry the person’s skin where the pads will be applied, and follow the voice prompts of the defibrillator. (See Unresponsive and abnormal breathing when a defibrillator is available.)

- Always access medical care for someone who has experienced a drowning incident and received CPR.

Education considerations

Context considerations

- Examine local health or accident data to work out which populations are most at risk of drowning in your region, for example young children, adolescents, or perhaps those with an underlying health condition or in a certain sociodemographic.

- Ensure an adequate risk assessment is carried out in advance of outdoor education activities. Draw up and apply a safety plan based on the risk assessment. The plan should include clear criteria for when to stop the educational activity because of risks or threats to learner safety such as lightning if outdoors, or an inadequate number of supervisors or lifeguards if near water. Evaluate the plan after the session.

- Using a mixture of both context-based learning (on a beach, poolside, lakeside, etc.) and more formal learning environments (online, a classroom, etc.) can be useful and complementary, allowing flexibility (e.g. for poor weather or accessibility). Teaching water competencies in a relevant context can allow learners to experience the local hazards and learn how to deal with risks in a realistic environment (e.g. children discover their beach or public pool; communities experience the dangers of the local pond or waterway). Some water competencies or elements of them are well suited to be taught in more formal environments either online or in-person.

- Prepare adaptable education sessions that can accommodate sudden changes in weather and water conditions. Teach learners to be aware of changing weather conditions, including fast moving or changing tides, and how to recognise and respond urgently to such changes to avoid increased risk of drowning.

Learner considerations

- Learning rescue techniques is encouraged from school-age, and knowledge and skills should continue to be refreshed and practised throughout a person’s life if these skills are to be retained.

- Adjust the focus of education depending on the learner group. For example, education to caregivers who live near to water could focus on prevention strategies, rescue and CPR, while education to children may focus on self-rescue skills and providing flotation.

- Consider that some people with underlying health conditions (epilepsy, heart problems or autism) may be more at risk of drowning (Denny et al., 2019).

- Change caregivers’ attitudes about the value of supervision by using context-specific examples.

- Some learner groups believe myths related to drowning so take time to sensitively dispel the myths and construct accurate knowledge. One common myth is that water is an airway obstruction you have to remove from the person (e.g. by swinging the person around by their legs, hanging them upside down or doing abdominal thrusts). In fact, there is no evidence that water acts as an obstruction. Rescue breaths and chest compressions can be started on an unresponsive person who is not breathing without delay.

Facilitation tips

- When appropriate, consider providing water safety messages as part of a broader practical programme aimed at developing water competence. Evaluate the programme to determine its effectiveness.

- Design programmes using behaviour change models, clearly identifying the risk factors you are trying to reduce.

- Design programmes with consideration of the local water hazards (including fast-changing weather conditions or tides) and cultural considerations such as myths that may affect behaviour change.

- Deliver water safety sessions using educators who can culturally identify with learners as this may make education more effective.

- Use hands-on (experiential) learning when and where safe to do so. (See the point above in ‘context considerations’ on risk assessment.) Give active opportunities to learners to practise how to develop competencies such as throwing a flotation aid.

- Ensure water safety messages are simple and visually engaging.

- Emphasise to learners that the motivation to go to a person in distress, especially of relatives and friends, exposes the first aid provider to a significant danger of drowning that can lead to death. The rescue should be provided at the lowest risk to the first aid provider. Flotation is essential to any water rescue.

- Practice safely throwing floatation devices (such as life jackets) or using locally available objects such as long tree branches to pull a person to shore. Education could include the use of improvised and purpose-made rescue equipment and should be repeated regularly.

- Where you are using a rescue device, discuss the dangers of the device such as the rescuer being pulled into the water, and how to avoid this happening.

- Emphasise that rescue breaths are the most important initial treatment to restore oxygen in the body and stop the drowning injury. Rescue breathing should begin as soon as possible (i.e. when the first aid provider reaches a safe place with a stable surface). Concerns of water in the airways should not delay rescue breaths – the rescue breaths will push any water in the airways down into the lungs.

Facilitation tools

- Consider using Media learning as part of a multi-approach to inform people of the risks, safe behaviours and how to access help.

- Use the Water Competencies checklist to ensure you include physical, cognitive and attitudinal elements to provide a holistic approach to water safety education.

- Find more facilitation tools in the Water context topic.

Learning connections

- Highlight and practise the connections to the Unresponsive abnormal breathing topics for baby and child or adolescent and adult, raising awareness of the importance of rescue breaths combined with chest compressions for people who are not breathing as a result of drowning (as opposed to chest-compression-only CPR).

- A person who has been in the water may be at risk of Hypothermia.

- If relevant, pair this topic with other aquatic topics such as Decompression illness or Aquatic animal injuries.

- Consider any relevant education practice in the topics of Water context, Media learning and Online learning for adults or children.

- Consider pairing water competency education with environmental or WASH (Water, sanitation and hygiene) issues.

- Care for the person’s mental distress, see Traumatic event.

Scientific foundation

Systematic reviews

Recognition of drowning by a lay-person

A systematic review on the recognition of drowning including the visual cues or signs a layperson can use to identify a drowning person was conducted and identified 23 studies (Pascual-Gomez & Petrass, 2020). The review highlights there is very limited empirical data describing how laypeople recognise a person is in the early stages of the drowning process. The review therefore also draws on limited data describing how lifeguards recognise drowning.

One study found that lifeguards are commonly taught to look for a specific set of behaviours that are considered to show drowning or distress situations, including splashing, frequent submersion, changes in body position, impairment of swimming effectiveness, and a lack of progress through the water.

Another study found that given the drowning person’s rapid progression from distress to submersion, recognition of even earlier signs of distress is critical, for example, a swimmer moving slowly due to weakness, physical condition, or fatigue or moving into water beyond their skill level.

A separate study found that lay people were especially good at identifying even earlier events that can lead to drowning, for example, children performing dangerous activities, such as repeated submerging, horseplay, or going too far from shore. Lay people need to be educated on behaviours that characterise distress in the water or drowning.

Results indicate that a person shows some or all of the above behaviours in almost all instances of drowning. However, as these behaviours are common in water settings, it may be challenging for bystanders to recognise them.

No studies reviewed addressed the fact that some drowning people display no signs.

The review made recommendations based on the very-limited and limited evidence available as well as based on best practice and consensus expert opinion.

Water rescue equipment

A scientific review addressing the question of what the most effective types of aquatic rescue equipment for a layperson or bystander to use to rescue a drowning person was updated in 2019 (Beale-Tawfeeq, 2019). It reported a lack of evidence identifying which items can be recommended based on accuracy, buoyancy, the distance that they can be thrown, and ease with which they can be caught by the drowning person. Despite the limited data, the review puts forward the current recommendation of rescue equipment including throw ropes and lines and ring buoys for effective use by bystanders which seem to contribute to positive outcomes.

Bystander CPR

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Basic Life support task force carried out a scoping review on resuscitation and emergency care in drowning (Bierens et al., 2021). It included 65 studies, of which 19 observational studies were identified that discussed bystander CPR as an intervention following drowning. Statistically significant associations were found with improved neurological outcomes (two studies), survival (four studies), however other studies either found a positive trend towards survival, or no association. Three studies compared compression-only CPR with conventional CPR and all favoured conventional CPR with bystander ventilation in terms of neurological outcomes and survival. Based on this evidence, initiating conventional CPR which includes ventilation and compressions is recommended.

Automated external defibrillator use in drowning

The ILCOR scoping review (Bierens et al., 2021) searched for studies reporting impact on outcomes from the use of an on-site automated external defibrillator (defibrillator) in cardiac arrest due to drowning prior to the arrival of emergency medical services but no studies were identified.

Indirect evidence of defibrillator use was found from 15 observational studies. In four studies there was a range of defibrillator use in cases of suspected drowning prior to the arrival of EMS. In 12 studies it was uncommon to detect a shockable rhythm. Seven observational studies found that a shockable rhythm was not associated with the outcome of better survival. One study found there was an association between shockable rhythm and increased 30-day survival. One study found the use of defibrillators on boats in moderate sea conditions to seem feasible. One study with lifeguards reported the mean time from arrival to defibrillation was 62 seconds. There was one case of inappropriate shock delivered to a person in an asystole in one study, with no obvious consequences. There were no adverse events identified in any of the studies listed.

Oxygen use

The ILCOR scoping review also searched for studies about the pre-hospital use of oxygen following a submersion incident, but no studies were identified (Bierens, 2021). Indirect evidence from observational studies found associations between hypoxia, oxygen administration and worse outcomes. In the absence of specific research about the use of oxygen in drowning, ILCOR concluded that the existing treatment recommendation for oxygenation after the return of spontaneous breathing applies. This guides to avoid hypoxaemia and hyperoxia, using 100% inspired oxygen until arterial oxygen saturation or the partial pressure of arterial oxygen can be measured. If the person is breathing normally, supplemental oxygen with a target saturation of 94–98% for a person who has drowned may be used.

In-water resuscitation

Five studies were identified by the ILCOR scoping review on the topic of in-water resuscitation (Bierens et al., 2021). The evidence indicates that in-water resuscitation (composed of rescue breaths only) is very challenging and should only be attempted by highly-trained rescuers if it is safe to do so. Therefore, the emphasis for first aid providers should be on non-contact rescue rather than in-water resuscitation.

One clinical study used a protocol of giving up to one minute of ventilation before moving the unresponsive person to shore and in deep water required either the availability of a flotation aid or at least two rescuers. Initial survival, survival to hospital discharge and favourable neurological outcome were all rated higher for in-water resuscitation. The other four studies evaluated the capacity of lifeguards and laypeople to perform in-water resuscitation and rescue of a manikin. In-water resuscitation was technically difficult and physically demanding, particularly in open water. It increased the rescue time, number of submersions and breathing-in of water by the manikin. Some trained lifeguards and laypeople were unable to complete the rescue. ILCOR found that the use of ventilation adjuncts by well-trained lifeguards might facilitate in-water resuscitation.

Resuscitation on a boat

The ILCOR scoping review (Bierens, 2021) found seven studies that evaluated resuscitation on a boat. One case series looked at the outcome of survival from resuscitation on a boat (24 cases) and found no survivors. However, the CPR quality was reported to be sub-optimal. In the other case series, six resuscitations were attempted on a boat or lifeboat; there was only one survivor after one month. Four studies evaluated the capacity of lifeguards and fishermen to perform CPR in inflatable rescue boats or fishing boats. The studies showed that CPR was physically demanding but that resuscitation on a boat was feasible. The quality of the resuscitation was affected by the boat speed and the sea conditions with ventilations more affected than chest compressions. One simulation study showed that defibrillator use on rigid inflatable rescue boats on calm water was feasible.

Advanced airway management

In the ILCOR scoping review, no studies were identified that examined the effect of a particular airway management strategy over another or no intervention, in the management of a submerged person (Bierens et al., 2021). However, six observational studies indirectly examined airway management strategies in people following drowning events. In all studies, intubation was an indication of the severity of the injury, with the most severe cases being intubated during cardiac arrest or facilitated with anaesthesia. Two studies showed intubation was associated with worse outcomes and one study did not find an association between intubation and long term mortality. One study showed mobile medical team ventilation as associated with better outcomes.

Prognostic factors that predict drowning outcomes

In 2020 ILCOR updated the systematic review for prognostic factors that predict outcomes concerning drowning incidents such as duration of submersion, the person’s age, the salinity of the water, and water temperature, compared with no factors (Olasveengen et al., 2020). The review recommended that submersion duration be used as a prognostic indicator when making decisions surrounding search and rescue resource management or operations.

– Submersion duration

Studies were considered to look at survival with favourable neurological outcome for different lengths of time of submersion (short – less than 5-6 minutes, intermediate – less than 10 minutes, and prolonged – less than 15-25 minutes). All studies noted worse outcomes associated with submersion duration longer than 5 minutes. The 2020 update was consistent with the 2015 review which found that submersion durations of less than 10 minutes are associated with a very high chance of favourable outcomes, and submersion durations of more than 25 minutes are associated with a low chance of favourable outcomes.

For the duration of submersion, the review and meta-analysis identified:

- For short submersion intervals (less than five to six minutes) moderate-certainty evidence was identified from 15 observational studies for the critical outcome of favourable neurological outcome and a low-certainty of evidence. All studies noted worse neurological outcomes in people with submersion durations of more than five minutes. For the critical outcome of survival, low-certainty evidence was identified using six observational studies. All studies had an association between worse survival outcomes among people with prolonged compared to short submersion durations.

- For intermediate submersion intervals (less than ten minutes) there is moderate-certainty evidence based on nine observational studies for the critical outcome of favourable neurological outcome and low-certainty of evidence from two observational studies for the critical outcome of survival. All studies noted worse neurological outcome among patients with prolonged submersion durations compared with intermediate submersion durations.

- For prolonged submersion intervals (less than 15 to 25 minutes) there is low-certainty evidence for the critical outcome of favourable neurological outcome from three observational studies and very low-certainty evidence for the critical outcome of survival from a single study. Submersion of less than 20 or 25 minutes was associated with better neurological outcome versus longer submersion duration for adults and hypothermic children. Cases with a submersion interval of fewer than 15 minutes had a higher overall survival rate.

– Age, salinity and water temperature

For age, salinity and water temperature there was very-low-certainty or contradictory evidence for the critical outcomes of favourable neurologic outcome and survival.

– EMS response interval

For the critical outcome of survival, there is low-certainty evidence from two observational studies. EMS response intervals of less than ten minutes were associated with better survival outcomes.

– Witnessed status

The review found that the definition of witnessed compared with unwitnessed drowning was inconsistently defined in the studies reviewed. It was often unclear if the term “witnessed” related to the submersion or the cardiac arrest.

For the critical outcome of survival with favourable neurological outcome, there is very-low-certainty evidence from three observational studies, showing better outcomes for witnessed drownings. However, the studies did not indicate submersion duration which has been identified as an independent indicator of prognosis.

For the critical outcome of survival, there is low-certainty evidence from four studies. The evidence is variable and contradictory, and one study could not be generalised.

Non-systematic reviews

Water rescue equipment

The scientific review outlined above by Beale-Tawfeeq (2019) addressing the question of the most effective types of aquatic rescue equipment for a layperson or bystander to use to rescue a drowning person also recorded some expert opinion. It recommended that teaching rescue skills should become a part of water safety classes and guidelines to reduce the rates of drowning. It also recommended that targeted interventions are needed to address rescue skills in multiple aquatic environments, particularly those that are high risk. And that the development of public-access safety programs may help improve drowning outcomes.

Finally, the review also reflected on the sentiment of “rescuer altruism” in a layperson or bystander when a person needs rescue from the water; they will initiate rescue despite the danger to themselves.

Lay-rescuers techniques in drowning incidents

A scoping review (Barcala-Furelos et al., 2021) to identify the safest techniques and equipment for an untrained bystander to use when attempting a water rescue included 22 studies. The review identified three types of techniques used by laypersons:

- non-contact techniques for rescue out the water: throw and reach

- non-contact techniques for in-water rescue using flotation aids

- contact techniques for rescue in the water: swim and tow with or without flippers

It stated that the safest technique for a lay-rescuer is the first one – to attempt non-contact rescue using a pole, rope, or flotation equipment without entering the water.

Despite the recommendation that an untrained person should not enter the water to rescue a drowning person, the literature shows a human tendency towards “altruism” in helping a drowning person. In most incidents, a rescuer entered the water and made contact with the drowning person, putting themselves at risk. This behaviour was especially manifested when the rescuer had a close bond with the drowning person. However, in many cases, witnesses took risks to help someone they didn’t know, based on the principles of the Good Samaritan and the desire to “do the right thing”.

The review suggests it may be difficult to prevent the impulse of lay-rescuers to enter the water but it is possible to encourage potential rescuers to carry some sort of flotation aid if they attempt a rescue. Studies in the review identified that the teaching of rescue techniques in school should be ongoing if the skills are to be retained in adult life.

Removal of fluid

There is no indication that water blocks the airway as a foreign body. Manoeuvres such as abdominal thrusts to relieve foreign body airway obstruction are therefore not recommended for people who have drowned (International Life Saving Federation, 2016). Such manoeuvres are unnecessary and may cause injury, vomiting, and delay CPR. Resuscitation with rescue breaths should begin immediately rather than attempting to remove fluids from the airways.

Little, if any fluid can be removed from the airways by drainage techniques (suctioning, abdominal thrusts or postural drainage). This is because the estimated amount of water breathed in is small and, after just a few minutes of submersion, it is absorbed into the circulation (Golden, Tipton & Scott, 1997). However, autopsy studies show large amounts of swallowed water in the stomach. Therefore procedures for foreign body airway obstruction should be used only if the airway is completely obstructed by a solid object.

Positioning of an unresponsive person who is breathing

Szpilman (2012) recommends placing the breathing person on their side in the recovery position, with their head positioned to allow free drainage of fluids. The position should be stable, without pressure on the chest.

Spinal injury in instances of drowning

A person who is drowning is at risk for a spinal injury only if they have also sustained a traumatic injury or been involved in a high impact activity (such as diving, water skiing, surfing, or being caught in moderate to severe surf breaks). Routine spinal immobilisation does not appear to be warranted solely on the basis of a history of submersion (Watson, 2001).

The International Life Saving Federation (2016) recommends that in the case of drowning as a result of a traumatic injury, if the person is unresponsive, management of their airway takes priority over any suspected spinal injury. The person can be handled to minimise spinal movement if possible. If the person is responsive, the principles of minimising movement apply and if removal from the water is necessary, then it should be done while maintaining alignment of the spine.

Education review

Prevention of drowning

A paper by Denny et al. (2019) summarised factors contributing to the incidence of drowning in the USA and then made recommendations to prevent drowning. These strategies to prevent drowning are particularly relevant to education and advocacy.

Factors contributing to drowning in the USA included the populations of young children 0-4 due to unsupervised access to bodies of water and adolescents who may overestimate their water competencies, undertake risky behaviour, or maybe affected by alcohol. Underlying health conditions such as epilepsy, cardiac arrhythmia and autism also increase the risk of drowning, with socio-demographics also a contributing factor.

The paper outlined that learning to swim is just one part of water competency. To prevent drowning, Denny et al. recommended that people need broader water competencies including knowledge of local hazards, understanding of one’s limitations, ability to put on a life jacket, and all the first aid related to drowning (recognition, rescue, etc). Developing these skills takes time and developmental maturity. The paper highlighted some existing drowning prevention strategies such as the Haddon Matrix and ranks five major interventions as evidence-based: 4-sided pool fencing, life jackets, swim lessons, supervision, and lifeguards.

Denny et al. went on to identify the role of parents, medical providers, pool operators and policymakers in being informed of and promoting drowning prevention recommendations and legislation. The paper identified the most evidence-based interventions as being four-sided pool fencing, life jacket use, swim lessons, supervision and lifeguards and bystander CPR.

The World Health Organizations “Drowning Prevention: an implementation guide” (2017) also formed much of the foundation for the prevention content. The paper provides practical steps to preventing drowning.

Lifeline rescues

Pearn and Franklin (2009) carried out a study with 25 volunteers which tested their ability to throw a lifeline (rope) to a person simulating drowning 10 meters from the shore. The time and accuracy of achieving a successful lifeline throw were recorded for each of multiple attempts. The results indicated that more than half of fit adults cannot throw a lifeline accurately to a distance of ten meters even with multiple attempts and that, in the heat of the moment, one in five “rescuers” do not anchor the end of the rope, which is then lost when thrown. These results were compared to competitive or trained rescuers who can deploy a lifeline with extreme accuracy and great speed.

The study highlighted the importance of the safety of the rescuer and the use of non-contact rescue to maintain this. However, it emphasised that to be successful in non-contact rescues, people need training and practise in throwing a lifeline or buoy. Pearn and Franklin implied that a person’s first time throwing a lifeline should not be in the midst of a life-threatening event.

Water competencies

Stallman et al. (2017) built on previous work on water competencies to use evidence to select essential water competencies. They argue swimming skills alone are not enough to address drowning prevention. Rather a broad range of competencies are required including:

- Safe water entry competence

- Breath control competence

- Stationary surface competence (buoyancy or treading water)

- Water orientation competence

- Propulsion competence (swimming)

- Underwater competence

- Safe exit competence

- Personal flotation device

- Clothed water competence

- Open water competence

- Knowledge of local hazards competence

- Coping with risk competence (awareness, assessment, avoidance)

- Assess personal competence

- Rescue competence (recognise and assist safely)

- Water safety competence (attitudes and values)

Water context

See Water context for more scientific foundation.

References

Systematic reviews

Pascual-Gomez, L. M., Petrass, L. (2020). Recognition of drowning by layperson. Unpublished manuscript.

Beale-Tawfeeq, A. K. (2019). Triennial Scientific Review: Assisting Drowning Victims: Effective Water Rescue Equipment for Lay-responders. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 10(4), 8. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1517&context=ijare

Bierens, J., Abelairas-Gomez, C., Barcala Furelos, R., Beerman, S., Claesson, A., Dunne, C., Elsenga, H.E., … & Perkins, G.D. (2021). Resuscitation and emergency care in drowning: A scoping review, Resuscitation, DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.01.033

Olasveengen, T. M., Mancini, M. E., Perkins, G. D., Avis, S., Brooks, S., Castrén, M., … & Hatanaka, T. (2020). Adult basic life support: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation, 142(16_suppl_1), S41-S91. DOI https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000892

Non-systematic review

Barcala-Furelos, R., Graham, D., Abelairas-Gómez, C., & Rodríguez-Núñez, A. (2021). Lay-rescuers in drowning incidents: A scoping review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2021.01.069

Franklin, R. C., & Pearn, J. H. (2011). Drowning for love: the aquatic victim‐instead‐of‐rescuer syndrome: drowning fatalities involving those attempting to rescue a child. Journal of paediatrics and child health, 47(1‐2), 44-47. DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01889

Golden, F. S., Tipton, M. J., & Scott, R. C. (1997). Immersion, near-drowning and drowning. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 79(2), 214-225. DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/BJA%2F79.2.214

International Life Saving Federation (2016). Medical position statement-MPS 21. Spinal injury management. Leuven, Belgium. Retrieved from https://www.ilsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MPS-21-2016-Spinal-Injury-Management.pdf

International Life Saving Federation (2016). Medical position statement–MPS 01. Abdominal thrusts. The use of abdominal thrusts in near drowning. Leuven, Belgium. Retrieved from https://www.ilsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/MPS-01-2016-Abdominal-Thrust.pdf

Stallman, R.K., Moran, K., Quan, L., & Langendorfer, S. (2017). From swimming skill to water competence: Towards a more inclusive drowning prevention future. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education: 10 (2) Article 3. DOI https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.10.02.03

Szpilman, D., Webber, J., Quan, L., Bierens, J., Morizot-Leite, L., Langendorfer, S.J., Beerman, S., Løfgren, B. (2014). Creating a drowning chain of survival. Resuscitation, 85(9), 1149-1152. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.05.034

Szpilman, D., Bierens, J. J., Handley, A. J., & Orlowski, J. P. (2012). Drowning. New England journal of medicine, 366(22), 2102-2110. DOI 10.1056/NEJMRA1013317

World Health Organization (2017). Preventing drowning: an implementation guide. Geneva, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/preventing-drowning-an-implementation-guide

World Health Organization (2020). Drowning. September 9, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning

Education references

Denny, S. A., Quan, L., Gilchrist, J., McCallin, T., Shenoi, R., Yusuf, S., … & Weiss, J. (2019). Prevention of drowning. Pediatrics, 143(5). Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/5/e20190850

Pearn, J. H., & Franklin, R. C. (2009). “Flinging the squaler” lifeline rescues for drowning prevention. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 3(3), 9. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1262&context=ijare

Related topics

Explore the guidelines

Published: 15 February 2021

First aid

Explore the first aid recommendations for more than 50 common illnesses and injuries. You’ll also find techniques for first aid providers and educators on topics such as assessing the scene and good hand hygiene.

First aid education

Choose from a selection of some common first aid education contexts and modalities. There are also some education strategy essentials to provide the theory behind our education approach.

About the guidelines

Here you can find out about the process for developing these Guidelines, and access some tools to help you implement them locally.